Tony Gregson's getaway-with two gold bricks

Published in Canada's Maclean's Magazine 1961

Tony Gregson, full name Anthony Hart Gregson, was the youngest son of Captain William Hart Gregson. Tony was born on Canvey in 1925. This is his story of how he became the most wanted man in Canada in 1954. Written by Ralph Hedlin who interviewed him and published the article in The Maclean’s Magazine in 1961. Republished here with the permission of Gregson’s neice Leonie Gregson.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“Stealing must be done with dash,” says adventurer Gregson, 36. “Do it well and you brighton a drad society.”

Switching lead bricks for gold ones, Gregson vanished from Yellowknife in 1954 with $54,000. It took the Mounties three years to find him By Ralph Hedlin

Tony Gregson solved the oldest quandary of the criminally inclined — how to steal a fortune and disappear to enjoy prosperity, reasonable entertainment and a life that is only slightly fugitive. He did it by stealing two gold bricks from a bush plane in the air between a gold mine and Yellowknife, NWT, in 1954. Together the bricks weighed 124 pounds—worth, at the mint price, more than $54,000. Gregson dealt it off in chunks sawn from the bars, when he needed cash. He took in, altogether, a bit more than the mint value. Then at the end of three easy spending years, he went to jail.

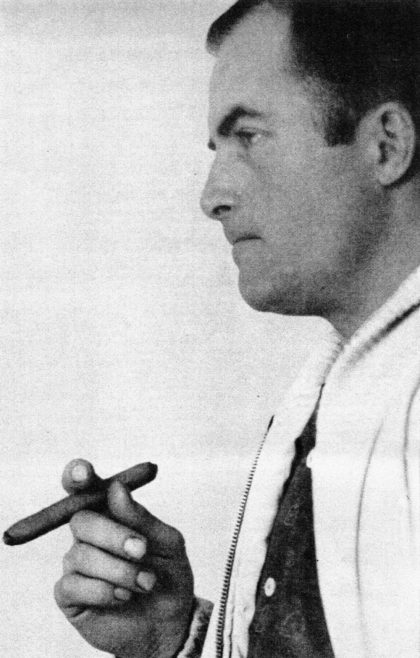

A few weeks ago I took a bush plane to Thompson, the big nickel-mining boom town in northern Manitoba, looking for Anthony Hart Gregson, who was not long out of prison. He was reported to be working on a drilling crew in Thompson. In the bunkhouses all the miners gave me the same story —Gregson had “pulled the pin” a month before and left no forwarding address, but the paymaster said. “He’s here. If a man has done time the boys’ll always tell a stranger he’s gone. If Tony isn’t in Hut II, look in the beer parlor downtown.” I found him in the beer parlor—a stocky, cleancut man with a scar under his right eye, the “distinguishing feature” described in posters that had been pinned up in hundreds of police stations and post offices across Canada. A few minutes later in my hotel room, Gregson, a big cigar in the corner of his mouth and a bottle of beer in hand, settled down to discuss what he called the gold-brick affair.

“Anybody who decides to steal should plan it with a bit of dash, and add a little color to our drab Canadian scene.” He looked out of the hotel window at Thompson. “This is a town that could do with some color,” he said, “it may be four hundred miles in the bush but it’s still just a dull suburb, an intellectual slum.”

I asked Gregson again, to tell me about the gold bricks, and this is the story as I put it together from what he said, what the Mounties told me and other records of the crime.

At fifteen, early in the war, Gregson joined the army in Britain. After the war, in which he served with a Scottish regiment and parachuted into Greece and later into France, he decided to emigrate from Britain, and chose a characteristically unconventional way to do it. He crossed to New York, as a stowaway aboard the Mauretania, crossed the border into Canada by crawling along the girders on the underside of the bridge at Niagara Falls, and got away with both escapades until railway police caught him boarding a westbound freight in Toronto and called the immigration authorities. But Gregson so impressed the immigration officers that they withdrew their deportation order, providing he stuck for six months in the job they found for him in a Toronto meat-packing plant.

Six months and one day later. Gregson left for Yellowknife. For three year he prospected in the Nahanni and Mackenzie valleys, panned gold, worked in mines and the bush, worked on a commercial fishing crew netting on Great Slave Lake. Once he saw a gold brick tossed onto a snowmobile at a mine site; a Métis laborer who wasn’t doing anything was ordered to run it the forty miles into town. More than once he saw gold bricks wrapped in their canvas sacks lying unprotected on the floor of bush planes for transport to Yellowknife. He began planning a robbery that would add color to the drab scene, “it was no trick to get hold of the bricks.” Gregson recalled later. “‘But how to jump those hundreds of miles to a big city without getting caught. That was the question” He began by having an Edmonton seamstress sew up heavy canvas drawstring bags to his specifications. For $25, a foundry made him a lead brick the same size and shape as a gold brick: later he bought $30.30 worth of lead from the caretaker of the inoperative Negus Mines at Yellowknife and made a second lead brick. He rented a cabin on the Negus property and stored his kit and canoe, the two lead bricks and canvas bags, and an ink pad and toy printing set he’d bought in Edmonton. He was almost ready. In the winter of 1953-54 he got work with Consolidated Discovery Yellowknife Mines, fifty miles by air from Yellowknife.

On July I, 1954, Consolidated Discovery poured its gold into two bars; one weighing 72 pounds, the other weighing 52. That day Gregson told James Engstrom, the mill superintendent, he was quitting and would leave on the Saturday plane. Max Ward, of Wardair Ltd., flew the plane, with a passenger in the co-pilot’s seat and Gregson and a third passenger in the seats behind. The men dozed as the plane droned south toward Yellowknife. The pilot left his seat only once, for a stop at a bush camp, and Gregson quickly exchanged his lead bricks for gold ones.

Ward clambered onto the dock at Yellowknife. Gregson right behind him. “Shove out those two gold bricks will you, Tony?” asked Ward. Instead, Gregson pushed out his Gladstone bag. Ward grabbed the bag. It clunked onto the dock.

“Jeez. Tony, what’s in there, gold bricks?” asked Ward. “Geiger” muttered Gregson and picking up his kit, he walked away. Before he disappeared he glanced back and saw the canvas-wrapped bricks lying on the dock, the documents pinched between. A truck would take them to the mine safe in the office of Frenchy’s Transport.

Once out of sight. Gregson hurried to his canoe, tied up nearby, and pushed off. He had everything—gas, food, tobacco, reading material—he needed to hide on the west side of the north arm of Great Slave Lake until the first storm blew over: then he would find his way down the Mackenzie River to the Liard and up to the Alaska Highway, or go down the Mackenzie to Rat River Portage and down the Bell and Porcupine Rivers and up the Yukon River to Circle, Alaska. Or he could go up the Hay River. There were several routes, and any one might serve as Gregson’s answer to the 600 miles that separated Yellowknife from concealment in a city.

The outboard motor wouldn’t start, and Gregson expected his lead-for-gold trick to be discovered within an hour at the mine office. He tore into the motor, but it was an hour before it fired and Gregson headed toward open water. By this time, since the police hadn’t arrived, he assumed the bricks had passed inspection in the mine office and were locked in the safe for the weekend, when they’d be taken out for shipment to Ottawa.

So Gregson changed his plan. He went to the new town of Yellowknife, phoned a cab driver to bring him a case of beer, and held court with several of his friends until the beer was finished. Then he took a cab to the dock, chartered a plane, and flew to the end of the highway at Hay River, an hour and ten minutes by air. Gregson checked into the hotel and went to bed, a tough day’s work behind him.

The town of Hay River is on the south shore of Great Slave Lake at the north end of the Mackenzie Highway. At noon on Sunday, Gregson bought a ticket to Edmonton and caught the bus to the south. Three hundred and eighty miles along the way, at Peace River, he left the bus and caught one going west to Prince George. Next he took the train to Prince Rupert, registered under his own name and stayed there four days until he could catch a steamer to Vancouver. Anthony Hart Gregson boarded the ship. Anthony Johnson got off.

Anthony Johnson registered in a Cordova Street hotel and claimed his first dividend. He bought a narrow-bladed hacksaw and, with radio blaring and the water running in the bathtub to kill the sound, he sawed off a chunk of gold. He sold it to a Chinese jeweller for a thousand dollars. The gold sawdust he brushed into an aspirin bottle to save for a day when he didn’t have two gold bars.

This is what happened, meanwhile, in Yellowknife. On Monday the office clerk in the transport office took the bricks out of the safe for shipment to Ottawa. The numbers on the canvas bags were 196 and 197. But he seemed to remember that the numbers of the documents recorded 195 and 196: he checked, found he was right, and got R. J. Kilgour, manager of the mine, on the radiophone. He told Kilgour they’d made a mistake in the numbers. Kilgour checked the numbers in his office. “The correct numbers are 195 and 196.” he said. “Weigh the bricks.”

The clerk came back to the phone. They weigh 48.2 and 43.2 pounds,” he said. “They should weigh 72 and 52. Something’s fishy,” said Kilgour.

The mine’s consulting engineer at Yellowknife, N. W. Byrne, and Corporal Bill Campbell of the RCMP dashed over to the office. Campbell’s first move was to see the men who had been on the plane. He had no trouble finding all of them except Gregson, and he soon found that Gregson had chartered a plane to Hay River on Saturday night. Campbell finally traced Gregson to the bus at Hay River, but no one had noticed him leave at Peace River. The search centred on Edmonton.

Then another complication arose. Gregson had drafted a letter in Yellowknife to the mine manager, Kilgour, in which, in a puckish mood, he instructed him to give any pay owing him to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelly to Animals. He addressed an envelope to Kilgour, stamped it and slipped it inside another envelope, which he mailed to a friend in the interior of British Columbia with instructions to mail the letter to Kilgour. When it arrived five days after the theft it created the impression that Gregson was in the B. C. interior.

By the time the police had switched their search to the coast, Gregson—hair cut, shaved, with a new suit and luggage and looking like any other prosperous businessman—was on the transcontinental train heading for Halifax. It was July 12. 1954.

“What was I thinking about? You know, I was thinking about the time we’d made camp on the shores of the Mackenzie River about a year before. I’d had a couple of belts of whisky and I’d told the prospectors with me that I was going to make one big steal and get clean away. Well, here I had a stack of gold on the seat beside me and I had no reason to think the back trail wasn’t very, very cold. I was thinking of what those prospectors would say when they heard it, because no one took me seriously.”

When, five days later, the train pulled into Halifax the RCMP had no idea where Gregson was and Consolidated Discovery Yellowknife Mines had no idea where 124 pounds of bullion had gone.

A few days later Gregson left the Lord Nelson, shifted a couple of bays down the Nova Scotia coast to Chester, and took rooms in the Hackmatack Inn. He decided to go into fishing and went to Lunenburg looking for a boat. In Glace Bay, on Cape Breton Island, he found a Newfoundland schooner-rigged jack-boat, complete with sail and auxiliary motor. It was seventeen tons gross, fifty feet long. The owner refused to take gold in payment, but Gregson managed to peddle ten pounds in Sydney for 3.400 U. S. dollars. He paid $1,800 for the boat, hired a crew, and ran it the three hundred miles around the coast to Chester. When he docked he paid off the crew and bought them one-way tickets on the bus. He went to his room at the Hackmatack and settled down with a book.

“I’ll never forget that evening. I was just getting ready to turn in when the landlady said there were a couple of men to see me and two RCMP constables came into my room. The gold was lying in my bag in the bottom of the clothes closet, and I figured it was all up. But all they wanted was to get some information on one of the men that had come down the coast with me. He’d broken into a drugstore and stolen an electric razor. They got the information they wanted and left, and I guess they don’t know until this day that they were within a couple of feet of Gregson’s gold.” He carried the gold down to his boat and buried it in the ballast.

Gregson didn’t make any money fishing, but this wasn’t known in Chester. He was fishing for swordfish and would go out with several cases of rum. Between parties the crew would catch some fish. He sold his catch in Halifax, and thus avoided any comment on the fact that his expenditures exceeded his income.

In the meantime the police were looking for him everywhere. “I worked on the Gregson case,” recalls a veteran member of the RCMP. “I don’t mind admitting that it was one of the most frustrating I’ve ever tackled. Once Gregson got out of the north there was nothing you could trace him by.

“There’s a routine in tracking down a wanted man,” he continued. “You check his friends and relatives and sooner or later a letter arrives or he shows. Gregson had just come to the country and most of his friends were in the bush. During the whole period he didn’t get in touch with his few good friends.

“You watch for any man living beyond his apparent resources, but Gregson did his high living, as we found out later, in Los Angeles, New Orleans, Florida, Cuba or the British West Indies. He’d drink quite a bit—he was picked up for drunken driving as Anthony Johnson and fined fifty dollars by the Ontario police —but he didn’t do enough to look unreasonably rich. He bought a six-year-old Fond”- instead of a Cadillac, which he could well have afforded. And he was a loner. He didn’t confide in anyone and be didn’t run off at the mouth. He didn’t have any regular women. And he split with his forner life. In place of being a prospector and mucker he became a fisherman.

“If you want to see a man who made a real success of blending with his background you look at Tony Gregson.”

The policeman was wrong on a couple of counts.

In the first place, Gregson did have a wench in Halifax, and another in Chester. In the second, he did see one of his old Yellowknife friends. It happened in the fall of 1954, when Gregson put up his boat and concentrated on converting some of his gold to cash.

“I took the train to Vancouver and went to one of my old stamping grounds, the bar in the Georgia Hotel. I was drinking hot rum in a kind of skull glass—a specialty of the bar—and looked across and there was one of my closest Yellow-knife friends drinking the same thing. It was good to see him. I had I big chunk of gold with me at the time and he helped me get into the Slates.”

Once across the border Gregson caught a bus for Los Angeles, where he sold three pounds of gold in a hockshop. In New Orleans he had the gold assayed— “it proved to be real good gold”‘ — and then went on to Key West for a week’s holiday. At the end of the week he crossed to Havana and began looking for a market.

He found it but didn’t trust his customers, so he cut the brick he had brought with him into slabs and hung them on shoulder straps under his clothes.

“I was afraid I’d get knocked off if I took the whole chunk. I sold it in $I,200 bites until I’d sold all I had and got about $35,000.”

Word spread that Gregson was peddling gold and the Havana police picked him up. “I gave the inspector in charge $1,0O0 and after five hours’ questioning they let me go.” Gregson claims.

The police suggested he leave Cuba and he took the advice. He crossed to Key West and took a bus north. Soon he was back at the Hackmatack Inn at Chester. Early in 1955 Gregson hired a crew and went into the bush to cut pulpwood. He took the remaining gold brick out of the hold of his boat and buried it in the woods. When he set out for a summer’s fishing he left the gold buried in the woods. In the fall he sold his boat in Portland, Maine, and flew to Nassau for a three-week vacation at the Windsor Hotel.

In Nassau, Gregson sat on the wrong side of the table in a crap game and, according to his story, “lost my bundle.” He used the return half of his ticket to get back to Miami and went by pulp boat to Corner Brook, Newfoundland, where he took a job with the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company and saved enough money to indulge his first love and make his first serious mistake: he went back to the mines.

The International Nickel Company hired him in Levack, Ontario, and he worked there for six months, and then shifted to Blind River. He bought a car during the year; in addition, he saved $2,200.

All this time his gold was lying in the woods near Chester. Early in 1957 he went to Chester, retrieved the gold, and took a bus to Miami. Living it up in Florida and the Caribbean, Gregson finally got down to the last of his gold, which he sold in Cuba for $15,000. He took another week’s holiday in Cuba, and one last week in Florida, and came back to Canada.

“That was an expensive week.” Gregson told me ‘I spent it at the Hialeah track and lost all my money.”

“You seem to be going out of your way to underline that you lost the money as soon as you sold the gold. Did you?”

“I did.” said Gregson. “All of it.”

“You’ve none of it left now?”

“None.”

Gregson’s weakness was a preference for the mines. He drifted back to Blind River, Ontario, and there he heard that the RCMP had been enquiring for a Tony Gregson. The police arrived twenty-four hours after he had gone.

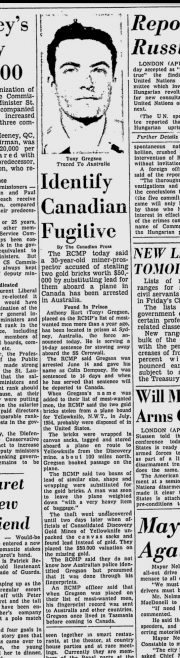

The Ottowa Citizen Paper dated Jun 20th 1957

By this time the RCMP had promoted Gregson to the list of ten most-wanted criminals. His picture had been in newspapers and periodicals. Tips flowed in and the police faithfully traced them down.

Once they thought they had him. A mucker in an Ontario mine, almost a double for Gregson, was picked up; he was released only when his fingerprints didn’t check. Finally the police tracked Gregson to the Hackmatack Inn. They arrived on February 26. 1957. Gregson had left on February 13. He had gone to Montreal and slipped unnoticed into the hold of a ship bound for Australia. He wanted to be sure the ship was well clear of the St. Lawrence before he was found, and he did without food and water for four days. Then he pounded on the hatch until the bosun let him out. When the police arrived at the Hackmatack Inn, Gregson was on the high seas.

The shipmaster tried to put him off at Curaçao in the Dutch West Indies and again at Panama, but the local authorities would not let him disembark. At Brisbane, Australia, Gregson jumped ship. The dock was quickly cordoned off and after twenty minutes of freedom, he was captured. He spent three days in jail while the ship unloaded cargo and then he was put on board to travel to Sydney. Here he spent fourteen days in jail while his fingerprints were run through the records of the ICAP—the international police organization of which Canada and Australia are both members. On the tenth day the police asked him if he was Tony Gregson, wanted in Yellowknife.

“I admitted it right away. You might as well be sporting about it when you’ve lost. But you know, the only reason they had my prints was because I got drunk in Yellowknife and started shooting out the lights with a .22 and another time pinched a truck.”

The final identification was made in Australia on June 14. 1957, just a few days short of three years from the time Gregson had hoisted the gold bricks.

He was met at Father Point, Quebec, on August 14 by Corporal Bill Campbell of the Hay River detachment of the RCMP and taken back to Yellowknife.

“We had a kind of funny conversation when I met Bill Campbell at Father Point. He said ‘Hi. Tony. It’s good to see you.’ I said ‘It’s good to see you,’ although it really wasn’t. Then Bill said ‘You’ve given us a long chase and a lot of trouble’ and I said ‘Give me the bit about The Mounties Always Get Their Man. Bill’ and he said ‘In the comic books they always do. Little tougher on the beat’. It was as though we’d been playing a game. Decent sort. Bill.”

The trial was set for August 19 in Yellowknife, and even here Gregson, in one sense did a salvage job. Terry Nugent, a lawyer from Edmonton and now a member of parliament, was sent north as prosecutor. He quickly detected a sneaking admiration for Gregson and his escapades among many of the Yellowknife residents from whom a jury would have to he picked. In addition the witnesses were scattered from Vancouver to Halifax. It would be difficult and costly to bring them to Yellowknife. He decided to try for a guilty plea.

Nugent met Gregson and his lawyer and indicated some of the evidence he would bring forward. He warned Gregson that he could get a ten-year sentence but predicted that with a guilty plea it would be only four or five years.

“I indicated more confidence in our ability to convict than I really felt. I was worried about a jury trial,” said Nugent.

Gregson had calculated the odds when he took the gold and he calculated them again when his case came before J. H. Sissons, judge of the Territorial Court. Anthony Hart Gregson, alias Anthony Johnson, pleaded guilty to hoisting a couple of gold bricks that did not belong to him. The prosecution urged leniency.

Mr. Justice Sissons sentenced Gregson to thirty months in prison. He was sent to the penitentiary in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, where he was a model prisoner until the early days of 1960, when he was released.

No prosecutions were brought against those who bought the gold. Most were beyond the jurisdiction of the Canadian authorities and it was impossible to get evidence against even those in Canada. It was accepted that all the money Gregson had raised from the gold was gone. If there was anything left at all, it was a little added color on what had always struck Tony Gregson as an unnecessarily drab scene.

Comments about this page

Hello Is it known if he is still alive? Sounds like quite a character. Regards Sparrow

The family do not know Sparrow

tony if you are still around get in touch with me we can go on another fishing trip to sable island but we will need another boat that does”t leak to much, no gold necessary you were a pretty good nice fellow little buddy hirtle

Add a comment about this page